I needed a suspension containing Legionella pneumophila. It needed to be a smooth suspension, in microbiology terms, single cells suspended in saline. Try this from an agar plate culture of L. pneumophila and the task is impossible. The colonies grow nicely enough but try to transfer colonies from the plate to a suspension and, oh dear! Very sticky, clumping that refuses to be suspended no matter how hard you try.

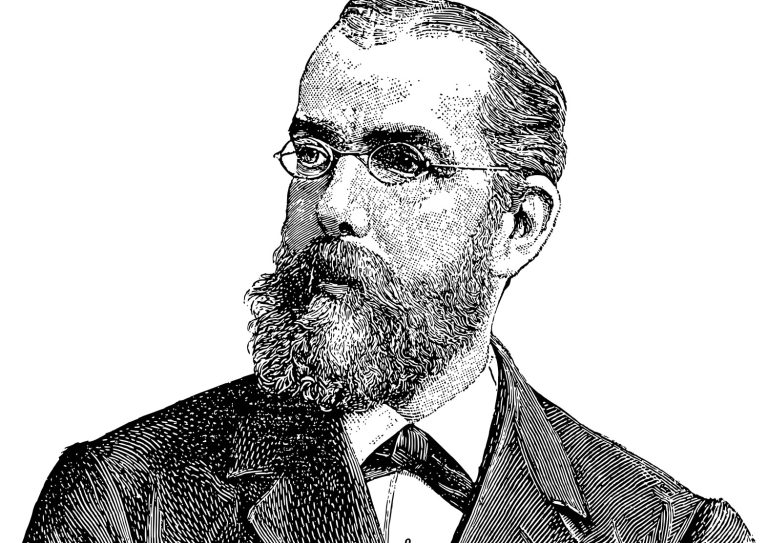

Causing a serious pneumonia and flu-like illness, the first known cases of Legionnaires’ disease were recorded at a conference of the American Legion in Philadelphia. Over 200 victims fell ill with cold and flu-like symptoms and 34 people lost their lives. It was in December 1976 that Dr Joseph McDade discovered and identified the bacteria, to be named Legionella pneumophila, as the cause of the disease.

One Saturday, around 1980, I drove 50 miles in my grey mini to Rotherham to attend a series of lectures. One of the presentations were given by Dr Tim Rowbotham from Leeds Public Health Laboratory. Tim described that his investigations on fresh-water amoeba showed that these free-living amoebae were a natural host for legionella organisms. This finding at the time was a dramatic one, first resulting in rejection of his scientific work, until his boss told the Editor of the learned journal that Tim’s evidence was for real and his work beyond doubt.

Why was this dramatic, in a science that had so many discoveries in the last hundred years or so? Because this discovery meant that in air-conditioning humidifiers (and other places) existed the perfect vehicle for transmission of legionella. As Tim described, the American Legionnaires that attended the conference in Philadelphia were not just breathing air contaminated with legionella bacteria but breathing in fresh-water amoeba in tiny, almost microscopic, water droplets. Amoeba that was packed full of hundreds, if not thousands, of legionella organisms ready to invade macrophages in the lungs of unsuspecting victims.

Presented with my sticky legionella problem, I remembered Tim’s lecture and called Leeds Public Health Laboratory. If anyone had an answer he would. “Hi Chris.” – I knew Chris and had worked with him for a few years earlier. – “I’m calling to see if I could speak with Tim Rowbotham.” “Well, not here and not right now” came his reply. Chris then added, “Tim is not in post any longer, the last I heard he has a hardware shop in Bradford.”

What does one do when given this information? Determined, I tracked him down and called him. “Hello, I’m trying to contact Tim Rowbotham please.” “Yes, how can I help?”

That evening we spoke at length, at the end of which I had all the information I needed. Back to the lab. With a month of development, the perfect solution emerged. Cultures of amoeba to assist in growing the legionella organisms. After a few days, when the amoeba couldn’t withstand the internal pressure, they ruptured giving up huge amounts of living, swimming, legionella organisms in perfect suspension ready for processing.

Unfortunately, I’m fairly sure that Tim never received the recognition he deserved for his discovery. You could argue that his was a discovery waiting to happen. Nonetheless, I will continue to say thank you Tim, it was a pleasure to briefly work alongside a true expert in your field.

At the time I needed advice, you were probably the only one in the country able to provide it.

Peter Kerfoot MSc FIBMS

March 2025